- Published:

- Friday 5 December 2025 at 10:18 am

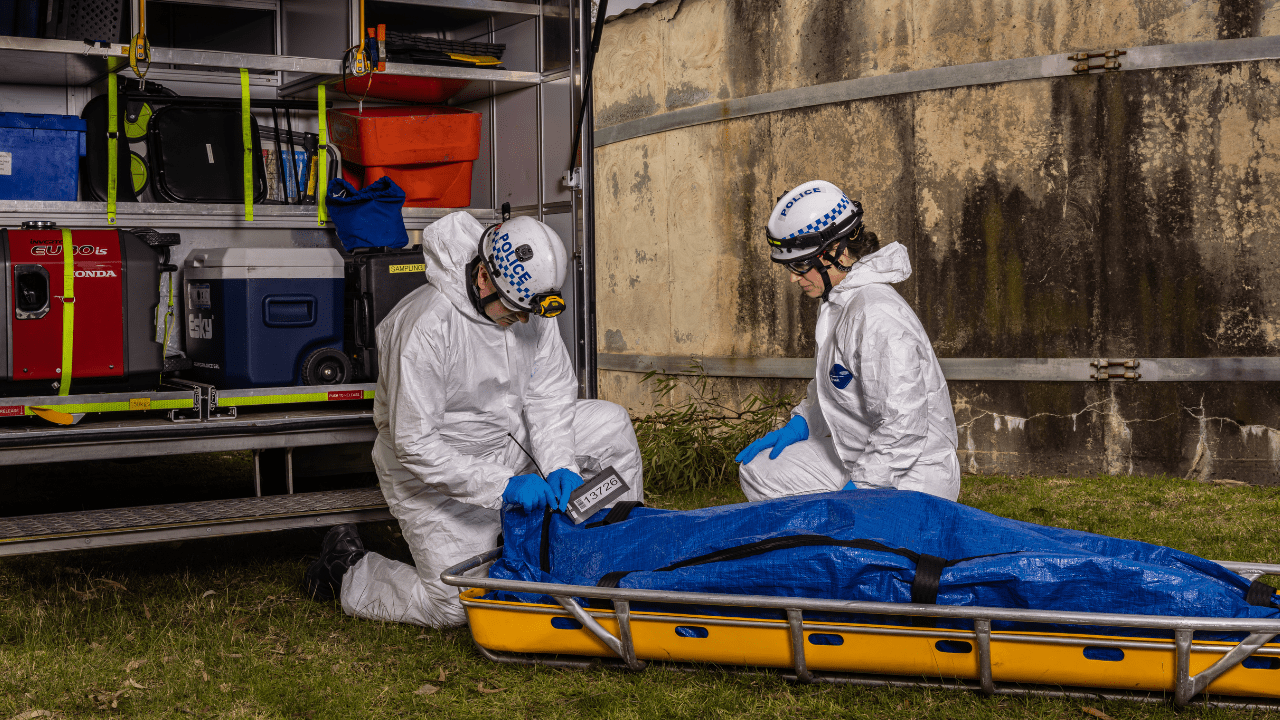

| Acting Sergeant Dani Oliverson and Leading Senior Constable Peter McClacharty from Victoria Police's highly-specialised Chemical, Biological and Radiological and Disaster Victim Identification (CBR/DVI) Unit. |

Closure from chaos

“It's a long time ago now, but it's still quite fresh in my mind.”

Those are the words of Leading Senior Constable Peter McClacharty as he reflects on the aftermath of the 2004 Thailand tsunami, where he worked and assisted as a police disaster victim identifier.

More than 5000 bodies were recovered in Thailand after the tsunami, which remains the world’s largest disaster victim identification operation.

Ldg Sen Const McClacharty has attended hundreds of local and international multi-casualty disasters during his more than two decades in Victoria Police’s Chemical, Biological and Radiological and Disaster Victim Identification (CBR/DVI) Unit.

He was a DVI responder at the 2022 Mount Disappointment helicopter crash, the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires, and the 2011 Christchurch earthquake.

Self-described as the “last man standing”, he is the only founding member left in the unit that was established in 2003 on the back of the terrorist attacks in the United States in 2001 and Bali in 2002.

Victoria Police wanted to ensure it was equipped should a similar human-created or natural mass fatality event happen in the state or across Australia.

In addition to mass casualty incidents, the unit is also called upon to assist with high-risk human remains recovery.

Although the DVI process isn’t required in these cases, the unit’s members have the skillset needed to identify and recover fragmented or disrupted remains for identification.

Real-life impacts

Ldg Sen Const McClacharty said sometimes it’s the smaller incidents that stick with him the most, like the death of two young brothers and their cousin in 2024 when the light plane they were travelling in crashed into a paddock and caught fire in Gippsland.

“The youngest victim was only 15 years-old and it happened so close to their family home and right before Christmas," Ldg Sen Const McClacharty said.

"It was devastating for the family who watched it happen.

“During the recovery process we could see them in the distance.

"They were mourning while we’re extracting their loved ones from the wreckage. It's always in the back of your mind, the poor family over there.”

The CBR/DVI unit are “world leaders” in what they do, according to Ldg Sen Const McClacharty, as it’s the only unit in Australia that has designated disaster victim identification and chemical, biological, and radiological response skilled members within the one unit.

Its members are highly trained to work with clandestine drug laboratories, potentially deadly substances, and suspicious powders aimed at causing maximum harm to the community.

Ldg Sen Const McClacharty recalls the anthrax attacks and threats that happened across the United States in the early 2000s as an example of when these skills are needed.

These incidents spawned copycat bioterrorism cases in Australia and other countries.

Honing their unique skills

It's this diversity of work that led Acting Sergeant Dani Oliverson to join the CBR/DVI unit in 2020.

Not long after joining the unit, A/Sgt Oliverson was lucky enough to learn more about DVI by attending training at the Australian Facility for Taphonomic Experimental Research (AFTER) in New South Wales.

The “game-changing” facility is the first of its kind in the southern hemisphere to study human decomposition under various conditions in the Australian climate.

The research undertaken at the facility helps forensic scientists and police with investigations.

This includes searching for, locating, recovering, and identifying human remains.

The facility also provides a controlled environment for training exercises for police and other investigators to aid skill development and searching techniques.

“Being new, this experience was incredibly invaluable," A/Sgt Oliverson said.

"It gave me exposure and a deeper understanding of the DVI process.

"It also offered insight on the incredible benefits of working alongside members from other police jurisdictions, including the Australian Defence Force, and New Zealand Police.

"Working together meant we could gain knowledge and learn from one another."

Stepping through training scenarios

A/Sgt Oliverson recalls one particular training scenario, involving a suicide bomber and a building.

“We had to work through the rubble methodically and meticulously in teams," she said.

"It was important to understand that the scenario was not only a DVI but a crime scene as well, meaning our primary focus was to search for intelligence such as mobile phones, computers, bomb related pieces et cetera.

"This kind of information is vital as it may assist in identifying the bomber or bombers, give an indication of the type of bomb detonated or if a secondary attack is imminent.

"Once that is completed our focus shifts to locating and recovering human remains, and personal property.

"It was incredibly fascinating.

“Before joining the police, I read a book called Death’s Acre, written by Dr. Bill Bass and Jon Jefferson.

"The book was about a Body Farm in Tennessee that was designed like AFTER.

"I thought it was the most interesting concept. I had no idea Australia had its own facility, let alone that I would one day be participating in a DVI scenario with real human cadavers 15 years later.”

| Acting Sergeant Dani Oliverson joined the CBR/DVI unit in 2020, enticed by the diversity of work that the team undertakes. |

Identifying victims

Although “fascinating”, DVI is challenging work that requires you to expose yourself to traumatic scenes and human bodies in different sorts of conditions, according to A/Sgt Oliverson.

“You have an important role - there is a job that needs to be done," she said.

"At the time, for me, I push aside the mental, physical, and emotional challenges so I can provide the dignity, respect, and care to those human remains to get them back to their families and loved ones.

"It’s not a job many people could do."

INTERPOL produced a four-phase globally accepted standard for DVI that is used to identify victims of human-created or natural mass casualty incidents.

This uniform approach makes it possible for DVI-qualified police to work internationally.

During the devastating 2009 Victorian bushfires, DVI responders came from as far away as Indonesia to assist with victim recovery and identification.

When an incident occurs, DVI members are among the first responders called to the scene.

The process starts with scene examination (phase 1), that involves the recording, searching and recovery of human remains and personal property.

Depending on the type of incident, where it occurred, and the conditions at the site, this could be a long process.

Putting training into practice

In 2022, Ldg Sen Const McClacharty and A/Sgt Oliverson worked at the helicopter crash site at Mount Disappointment, on Melbourne’s northern outskirts, from early morning until dark for four days.

“Bulldozers were required to clear a path for us to the crash site," A/Sgt Oliverson said.

"We were trekking through mud and overgrowth and were covered in leeches.

"There were countless challenges faced during this job - one of which was that the wreckage smouldering for days, which meant there were ‘hotspots’ in areas we needed to work in.

"After consulting with Fire Rescue Victoria, it was decided that they would lightly mist the hotspots with their hose.

"Unfortunately, this created a dangerous chemical reaction that released hydrogen cyanide gas, and we had to quickly remove ourselves and level up our personal protective equipment.”

Once the site was safe, it was a team effort for her, Ldg Sen Const McClacharty, and other DVI responders to extract the human remains and personal property of the five victims with “gentle, compassionate, and caring hands”.

After the recovery, post-mortem (phase 2) takes place where specialists examine the human remains and record features unique to each person.

These features include fingerprints, dental, DNA, and physical indications such as tattoos, scars or medical devices such as a pacemaker with a serial number.

Investigators will then gather information about the deceased from when they were alive as part of the ante-mortem (phase 3).

Evidence of unique identifiers will be obtained from the victim’s home, family members, and medical professionals.

During the final phase, reconciliation (phase 4), the post-mortem and ante-mortem data is compared to reconcile any two sets of data that appear to match.

Once a match is established, the Police Coronial Support Unit presents the information to an identification board.

Ultimately, it’s the Coroner who decides if there is sufficient data to prove an identity of a victim.

A/Sgt Oliverson said the team has added a debrief (phase 5) to the standardised INTERPOL process.

This gives members an opportunity to speak with police psychologists, as well as discuss as a unit ‘What worked well?’ and ‘What can we improve on?’.”

| Member of the CBR/DVI unit undertake extensive specialist training. |

Finding purpose among tragedy

As challenging as working in DVI can be, A/Sgt Oliverson said it’s a role that “gives me purpose in my ‘work life’”.

“I’m an empathetic person, so I always have in the forefront of my mind, ‘If this was one of my family members or a friend, how would I want them to be treated?’, especially when the situation is so traumatic and horrible,” she said.

“You're doing something that's not for yourself, it's for other people.

"No matter who they are or what the circumstance is, we are giving them peace by reuniting them with their loved ones.

“The reality is DVI work is taxing, there’s no doubt about it.

"That’s why it’s crucial you take full responsibility for managing your mental health as well as checking in on your work colleagues.”

When reflecting on his career in the CBR/DVI unit, Ldg Sen Const McClacharty said no two jobs he’s attended have ever been the same, but some could have easily been avoided.

“Some incidents you turn up to and think, ‘What a waste’,” he said.

He describes car accidents where someone could have paid more attention to their driving or avoided in-car distractions, but because they didn’t, their trip ended in tragedy.

“Now their family is grieving because of that lapse in judgement,” Ldg Sen Const McClacharty said.

He reiterated A/Sgt Oliverson’s statement that DVI work is not something that everyone can do, but working with a great team and the job satisfaction from helping families makes it worth it.

“If you’d said to me that I’d be doing this 21 years later, I would have laughed, but I'm still here and still enjoy it.”

To find out more about the broad range of forensics specialists at Victoria Police visit Forensic Services.

Editorial Emily Wan

Photography Jesse Wray-McCann

Subscribe to Police Life: Our people, our stories

Get real police stories delivered straight to your inbox. Come behind the scenes and get a rare insight into the life and duties of Victoria Police's workforce of more than 20,000 dedicated people.

Email policelife-mgr@police.vic.gov.au to unsubscribe at any time.

To find out more about our privacy policy and how we store information, visit our Privacy page.

Updated